For us, the word “recipe” began with the Latin verb recipere (to take). And many early recipes in the West indeed started with the instruction to “take” something, usually an ingredient.

Our verb “take” – as used in recipes, at least the old ones — implies violence, doesn’t it?

Let’s look at what the Oxford English Dictionary has to say on the subject:

The earliest known use of this verb in the Germanic languages was app. to express the physical action ‘to put the hand on’, ‘to touch’the only known sense of Gothic têkan. By a natural advance, such as is seen in English in the use of ‘lay hands upon’, the sense passed to ‘lay hold upon, lay hold of, grip, grasp, seize’the essential meaning of Old Norse taka, of MDu. taken, and of the material senses of take in English. By the subordination of the notion of the instruments, and even of the physical action, to that of the result, take becomes in its essence ‘to transfer to oneself by one’s own action or volition (anything material or non-material)’.

And at least one meaning directly relates to our discussion:

b. To catch, capture (a wild beast, bird, fish, etc.); also of an animal, to seize or catch (prey).

And a look at Webster’s, too, just to cinch the matter, turns up the following:

transitive verb 1 : to get into one’s hands or into one’s possession, power, or control: as a : to seize or capture physically <took them as prisoners> b : to get possession of (as fish or game) by killing or capturing c (1) : to move against (as an opponent’s piece in chess) and remove from play (2) : to win in a card game <able to take 12 tricks> d : to acquire by eminent domain

“Take” takes on a wholly different sense as the tie to violence emerges. The tools of the kitchen — knives, for one — permit other acts (burn, boil, strain, wring, pound) beyond “taking.”

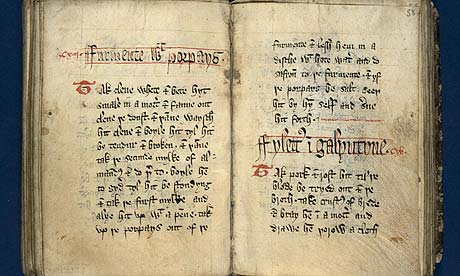

A most fascinating article came my way recently, “Text-types and language history: the cookery recipe,” by Manfred Görlach, buried at the end of a highly technical tome called History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics, edited by Matti Rissanen et al. (Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992).

As complex as this chapter is, it adds a lot to our understanding of the evolution of cookery books.

Görlach analyzes recipes beginning with Old English and ending with Charles Elmé Francatelli and a couple of Anglo-Indian cookbooks. Though he says no “extant” cookery books stem from the Old English period, he does take (there is that word again!) as an example a text, a recipe as it were, for curing baldness from a medical treatise by Plinius, in keeping with the tendency for later cookery books to include medical information. Listing the major words in the text, Görlach presents the following, listing the imperative form of verbs predominated in this instructional genre with its transitive verbs (burn, boil, strain, wring, pound — all words we still use!):

Genim (‘take’ [or ‘grasp’]) N (dead bees);

gebaerne (‘burn’) Ø (‘them’) to ashes; and also linseed;

do (‘put’) oil on thatseode (‘boil’) Ø long over glowing coals

aseoh (‘strain’) Ø then and awringe (‘wring’) Ø and nime (‘take’) N (willow leaves)

gecnuwige (‘pound’) Ø (‘them’)

geote (‘pour’) Ø and pour ‘on the oil’

wylle Ø (‘let boil’) again for a while on the gleeds (glowing coals),

aseoh Ø (‘strain’)

then smire (‘smear’, ‘annoint’) with Ø after bath.

And Görlach also includes comments on the impact of historical social change on “linguistic structure” found in cookery books.

Genim (‘take’ or ‘grasp’) — such an interesting word. especially when white wine enters the discussion.

To be continued …

© 2009 C. Bertelsen