As Julian Barnes writes in The Pedant in the Kitchen, “In the old days the transmission would have been oral and matrilineal. Then it became written and increasingly patriarchal.”* Every cook follows a recipe when he/she first picks up the knife or the wooden spoon. It may not be written, it may be open to interpretation and change, but it’s still a recipe, a guideline for the way forward, a means to an end, the end being a dish on the ground, around a communal fire, or perched on a table draped with a freshly pressed cloth and festooned with gleaming silver forks and spoons. Without recipes, which essentially provide a basic structure for the cooking process, it would be hard to achieve constancy. That is not to say that I advocate slavishly following recipes, but I think it’s important even for people who say, “Oh, I NEVER follow recipes,” to understand that, yes, they ARE following recipes. Every dish cooked and/or created in the presence of heat, knives, and/or other processes IS a recipe.

But, like artists trained in classical techniques, cooks with an understanding and familiarity with the basics move on to the innovations that bespeak change.

The following is a story about the power of recipes, a testimony to the way ideas about cooking disperse and change lives.

*****

I once did not know what spaghetti sauce really should be. Or, better said, could be.

Now, of course, every Italian cook touts her own version. But that’s not the issue here. All of those myriad tomato sauces probably include real tomatoes in some form, maybe fresh woodsy-scented mushrooms, a pinch of salt, a grinding of pepper, leafy basil and pungent oregano, and heaps of plump garlic cloves slowly sautéed in glistening golden-green olive oil. After all, that’s what salsa di pomodoro is supposed to be, right?

With a well-made salsa di pomodoro, your taste buds stand up and sigh. Maybe they even cheer when you bite into a really great one. As you swirl your fork in the mound of pasta before you, the slightly tart but sweet sauce coats each strand of spaghetti, the smell of garlic slowly becomes stronger as you maneuver your fork toward your mouth. That first bite, when your lips surround the pasta like a deep kiss, ought to make you glad to be alive, to be experiencing the sudden rush of flavors. Your taste buds really should moan, especially when bits of freshly torn basil perfume the heavenly bite.

Unfortunately, my taste buds groaned when I ate my mother’s spaghetti sauce. First of all, we weren’t Italian, not even close. Generations of vegetable-boiling English dotted our genealogy in America, dating way back to 1632, leaving no hope at all of even a gentle French influence on the family culinary heritage. Unless you count the Norman noble named Pardieu who plundered and pillaged with William the Conqueror. Pasta was truly an exotic food in that meat-and-potatoes crowd. And it didn’t help an iota that my initiation into all things culinary took place during America’s 1950s love affair with the can opener. Casseroles ruled the food pages (then called Women’s Pages), much like the dinosaurs flourished eons ago.

So, you ask, what was this spaghetti sauce that I loathed so much?

Imagine, if you can, library paste approximately the color of Thousand Island dressing. If you can do that, congratulations, you’ve created a vivid mental picture of both the consistency and the color. Good. Not only was the mouth feel of this stuff offensively gluey, it also bubbled with large slightly cooked coarse chunks of celery and onions, adding more insult to the injury. Instead of melded flavors, I tasted the acridity of the onion and the fierce bite of essentially raw celery. Crunch, crunch, I could hear myself chewing as I ate. Of course, gray-tinged hamburger lurked in there somewhere, too. The library paste, produced by wedding a can of cream of mushroom soup with a can of tomato soup, cemented everything together into one very cohesive mass. Spices, you ask? Oh yes, salt and pepper. That was it.

So, you see, I really didn’t know what REAL spaghetti sauce ought to taste like. And so now you can also understand why I gagged when Mrs. Fryxell asked me to baby-sit one night and informed me that she would make spaghetti for the kids and me to eat, because they were going out to eat earlier than usual.

When I walked into their house later that week, the aroma of something fabulous filled the air and saliva surged around my tongue. Hmmm, maybe this would be good, I thought.

It was.

So good that I begged Mrs. Fryxell to write down the recipe for me. Wine and real Italian spices (dried, but what the heck—this was pre-food revolution America!)! I loved that spaghetti!

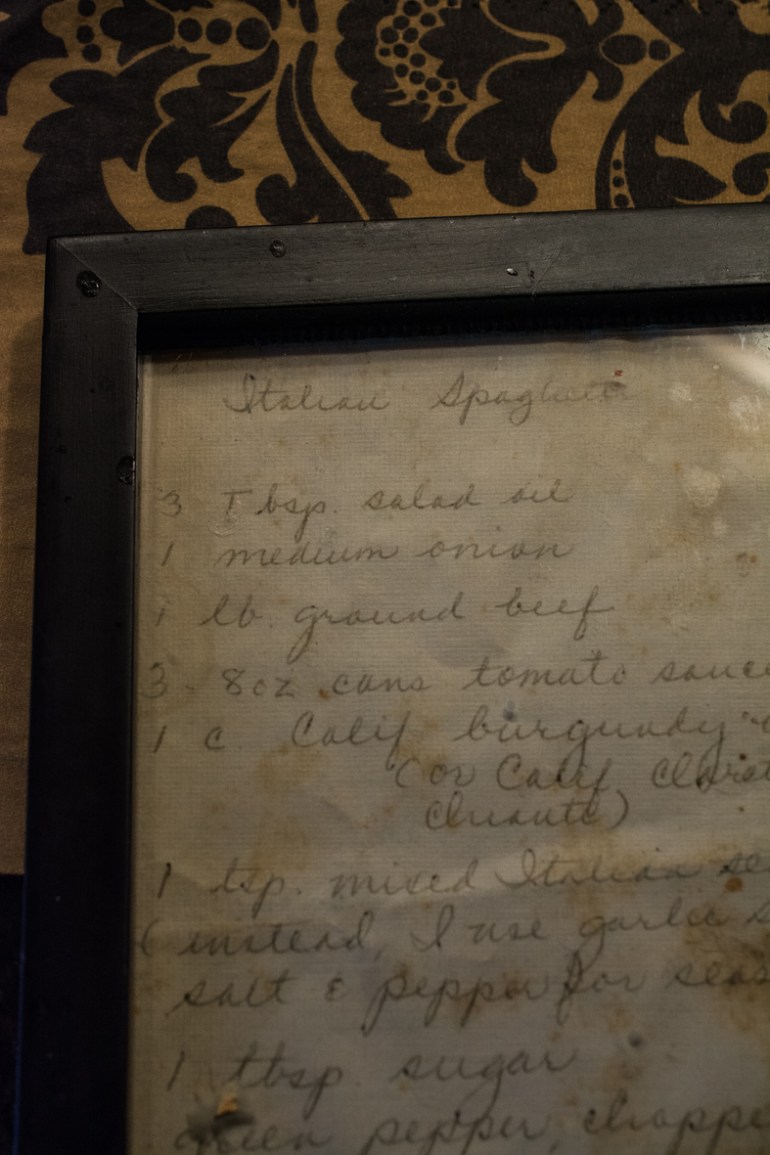

Such an epiphany was Mrs. Fryxell’s spaghetti sauce that the-now-tattered scrap of paper on which she scribbled the recipe hangs in my kitchen, properly framed in a small black frame and protected from the elements. And for my meat-and-potatoes family, I cooked that sauce for more nights than I can remember, a true salsa di pomodoro. Or at least a recipe worth keeping and fiddling with.

Never again did we ever suffer library-paste spaghetti sauce in my house.

Mrs. Fryxell’s Spaghetti Sauce

3 Tbsp. salad oil

1 medium onion

1 lb. ground beef

3 8-oz cans tomato sauce

1 c. Calif. burgundy wine (or Calif. Claret or chianti)

1 tsp. mixed Italian seasoning (instead I use garlic salt, salt & pepper for seasoning)

1 tbsp. sugar

green pepper, chopped

½ lb. (2 c broken) spaghetti

1 c. grated cheese

Make as usual.

So I did. Make as usual. That is, until I could buy fresh herbs and full-bodied Cabernets, extra-virgin olive oils with a peppery bite, and Parmesan cheese so nutty in flavor it seemed a sin to do anything but eat shavings right off the knife.

*Barnes, Julian. The Pedant in the Kitchen. Atlantic Books: London, 2003, p. 13.

© 2014 C. Bertelsen

Yes, after a while the recipe books turn out to be like road maps, don’t they? (Except for baking, where one must normally quite exact with crusts and cakes, but not with flavorings or fillings, etc.)

I love this! The title caught my eye. I used to follow recipes religiously and save all the ones I loved. Then I developed a curiosity for the science and chemistry behind the cooking processes and I started to develop my own recipes – I have so much fun experimenting in the kitchen! Happy to have found your blog! Cheers

Yes, indeed. And perhaps she thought she was making something really interesting?

Thanks, Merril. The mater’s sauce indeed insulted the very idea of marinara, but at least we had something to eat, one way to look it, no?

Yes, Tony, most tomato-based pasta sauces nowadays taste better with canned tomatoes!

Canned is not necessarily bad. I like Elizabeth David’s method of making tomato sauce (baked slowly whole, and then sieved). It does give a very fresh taste. But only with home-grown tomatoes.

Even the best vine-ripened supermarket tomatoes don’t taste quite so good in a sauce. But, then again, the supermarket varieties are chosen for shelf-life.

For flavour, and for 1950’s ease of use, I use canned San Marzanos : http://www.consorziopomodorosanmarzanodop.it/

(No, it’s OK, it comes in both IT and EN)

I loved this: “With a well-made salsa di pomodoro, your taste buds stand up and sigh. Maybe they even cheer when you bite into a really great one.” And your poor taste buds groaning at your mom’s ghastly sauce. I have to say, it sounds truly awful. Thank goodness for your gustatory epiphany at Mrs. Fryxell’s!