Reading a recipe, preparing and consuming it are, in the end, the word and the body become one.

~ Janet Theophano, Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote, p.280

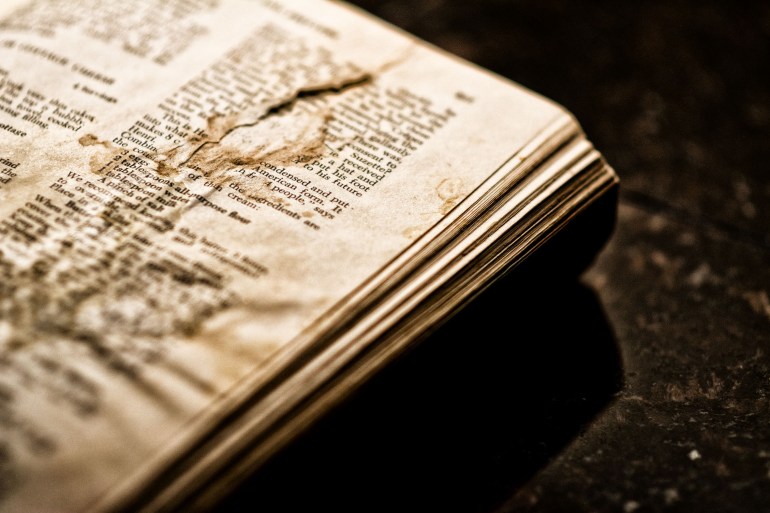

I sat there, the long wooden table shining like a mirror in front of me, half listening, watching the wind-blown trees through the windows of the old stone-walled library. The sound of a fist slamming the table startled me and I sat up straight and stared at the man at the head of the table. “I won’t stand for it,” the new head of the office yelled. “I don’t want to see any more dirty recipe books added to the collection. We have enough of those useless things as it is. They’re like hash, a big mess!” A moment of absolute silence hung in the air like an ill-placed burp. The twelve angry women scrunched around the table all looked at each other with tight, pursed lips. Then someone – not me – spoke up firmly, “Sir, these books testify to a lot more than mere hash.”

Hash, with its rather unpleasant companion word “rehash,” conjures up visions of an unholy mess, a quivering glop of leftovers slipping around on a plate, a dish best unseen and stuffed into a “coffin” (or to use the archaic use of the term, pie crust). Quite unappetizing.

And yet there is a method to the madness.

Recipes, on their own or in books or manuscripts, convey worlds of knowledge and information. It just takes a different way of seeing and thinking to realize this.

Although they appear to be like a mess of hash, recipes were quite clear during the Middles Ages and later, when written recipes served as aides memoires to cooks and stewards charged with the orchestration of enormous feasts and banquets for their wealthy and royal masters. Changes occurred over time: instead of seemingly random placement of recipes on scattered pages, when printed cookbooks proliferated and became the norm, authors and printers first grouped recipes according to type, be it soup or meat or sweets, and then later by order of serving. Although nowadays apparently obvious, the structure and arrangement of recipes in cookbooks is anything but.

Recipes turn out to be complex, with individual words conveying tremendous a priori knowledge. As Tomlinson writes, “A recipe in a cookbook is embedded in a nest of assumptions, prior cultural and technical knowledge, connections between types of instructions, and the ability to bridge all of these so that the recipe can be followed.” (1)

Just about everyone who reads about food these days knows that the word “recipe” grew out of a Latin word, recipere, meaning “To take,” as well as “To receive.” In my youthful enthusiasm for cookbooks, I mistakenly wrote receipe over and over again, driving my mother toodling crazy. Until, that is, during a visit to Charleston, South Carolina, she happened to come across a copy of Charleston Receipts. And saw the light. She inscribed my now-tattered copy: “Dear Cindy, you were RIGHT!”(2)

Well, almost.

Webster defines “recipe” as 1 : PRESCRIPTION 2 : a set of instructions for making something from various ingredients 3 : a formula or procedure for doing or attaining something

In other words, a recipe is a set of rules. (And rules are always meant to be broken, right?)

Most recipes from the early days of cookbookery tended to fall into the category of medicinal and health-related categories, not an unusual situation. Even in China, far removed in time and space from medieval Europe, the word for food is “fang,” also in the sense of a medical prescription. The invalid or sick person was instructed to take the concoction according to the instructions. And the idea of recipes conjoined with instruction remains one of the major driving forces behind the surfeit of cookbooks in modern global culture.(3)

Thus the reason why so many old receipts start with the phrase “Take … whatever.”

And that leads me to start with ingredients, the stars of any recipe, because any recipe essentially instructs me to “Take” something, which can only mean the bounty of the garden, the market, or the larder, crocks filled to the edges with fermenting cabbage. Or perhaps a haunch of fresh beef, chicken pieces, or a whole goose. Perhaps the most disturbing recipe I have ever read – and I have read many – comes from the 7th edition of eccentric English cookery writer Dr. William Kitchiner’s The Cook’s Oracle and Housekeeper’s Manual (1830, first published in 1816), “To Roast a Goose Alive”:

“Take a GOOSE or a DUCK, or some such lively creature, (but a goose is best of all for this purpose,) pull off all her feathers, only the head and neck must be spared: then make a fire round about her, not too close to her, that the smoke do not choke her, and that the fire may not burn her too soon; nor too far off, that she may not escape free: within the circle of the fire let there be set small cups and pots full of water, wherein salt and honey are mingled: and let there be set also chargers full of sodden apples, cut into small pieces in the dish. […] (4)

Overshadowed by Eliza Acton (Modern Cookery for Private Families, 1845), Dr. Kitchiner nonetheless deserves far more recognition, BECAUSE IT WAS HE who first incorporated specific quantities of ingredients into recipes. Kitchiner added marketing tables based on seasonality as well. Acton first listed ingredients before the method and she also placed those ingredients in the lists in order of their usage in the recipes. These features appear in many, if not most, of the modern cookbooks that lie scattered everywhere in my house today.

Like the horrifying goose recipe mentioned above, most recipes – then and now – include a name, ingredients, and method, as M. F. K. Fisher reiterates in her essay, “The Anatomy of a Recipe.” (5) This formulaic approach serves quite well to get the message across, reminding me that cookbooks might be considered among the first “how-to” books. And another thing about cookbooks: they tended to be strongly associated, at least in the beginning with urbanization more than with rural areas. Not just because cooks in rural areas may well have been illiterate, though there’s that, but because in urban areas, the breadth and reach of ingredients might well have been far wider than is rural areas. Shops and markets, close to the shipping docks, made a difference in what went into the pot. (6)

There’s something rather unsatisfying to me these days about cookbooks that contain just recipes with terse titles, lists of ingredients, and a description of the method for making the dish. Where’s the chatty headnote, filled with cultural references and requisite adulation of the Tuscan or French countryside? The story telling all about Mrs. So-and-So who gave up her exclusive culinary secrets to the author? Yet this spare style is exactly what recipes looked like in various early books such as The Book of Sent Soví, a Catalan cookbook dating to the mid-fourteenth century. In The Cookbook Library, Anne Willan traced the evolution of recipe writing through the ubiquitous “white eating,” or “blancmange.” (7) Here I wish to briefly examine some trends in recipe writing, via an examination of two meat stew recipes.

This first recipe comes from The Book of Sent Soví; the book appeared in print in 1979, although it was copied and plagiarized for centuries:

XXXVII

Meat Stew

If you want to make meat stew, make a good broth of mutton and chicken. Then take undercooked mutton legs, with the lean part chopped up, and fatty salt pork, fresh pork, and grated bread, as much or a little less than the meat. Put it in a pot to cook with the fatty broth. And when it has thickened, flavor it with salt, and take it from the fire. And take beaten eggs, two for each bowl, with some stew, and put it in the pot, mixing well. And color it with saffron. (8)

What do I learn when I look at this recipe? I learn that fresh mutton and chicken were available, that the cook would have preserved some pork fat using salt. I also find out that bread can be grated and people used it for thickening; eggs also served the same purpose. Knowing how to cook as I do, mostly European food by dint of my place on the planet, I realize that these last two are still used commonly as thickeners. As for cooking the recipe, I need to know how to make a broth with mutton and chicken, how to flavor it. Then I must add the chopped meat, possibly the bone-in remains of the legs, the salt pork, and grated bread, likely old scraps. Over a slow fire, I will boil down the broth to thicken it, along with the bread, seasoning it all with salt to taste. The number of eggs depends upon the number of servings I suspect I will get from the stew. At the end I toss in some saffron to enhance the no doubt grayish color of the broth, flavoring it as well in the process.

Now turning to Lady Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book (1604), I find this:

TO STEW MUTTON

Take a legge of mutton boyle it in water and salte until it bee almost boyled, then slice it in pretty bigge pieces, put it in a dish save the gravie w’h the muton, and put some white wine and a little grose peper unto it, soe let it stew till it bee almost ready, then beate the yelkes of three egges w’h some wine vinegere and put to it stir it still after you have put in yo’ egges, then serve it upon sippets and slice a limond smale the meate and rinde & stir it amonge it, but you must not stue it w’h the rest, for it will cause yo’ limonde to tast bitter. (9)

With this recipe, I am to boil the meat until it’s nearly done (tender?), then slice it and place it in a shallow dish. The next step tells me to add wine and pepper to the stock remaining in the pot. Egg yolks thicken the stock somewhat, poured over the meat and topped with lemon slices. Lady Fettiplace cautions that cooking the lemon slices with the gravy would cause it to taste bitter, which is true if the peel is left on the lemon. It could be that she wants to rind removed, but it is not completely clear.

Both recipes here require similar procedures – boiling and thickening the sauce (gravy) with eggs. The second recipe is a bit more complex, but both recipes require some idea of quantities and both instruct the reader to carry out certain tasks in order to arrive at the finished dish. I actually can picture the finished dishes, for they resemble quite closely fricassees, as well as modern recipes for Agnello Brodettato (Lamb Stew).

So, old cookbooks – stained, scruffy, or not – offer much to contemplate.

Hash? No, not at all.

References:

(1) Tomlinson, Graham. “Thought for Food: A Study of Written Instructions.” Symbolic Interactions 9: 201-216, 1986, p. 205.

(2) According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first use of the word for a food recipe appeared in 1595 in Widowes Treasure, in conjunction with directions for making Ipocras.

(3) Tomlinson, Graham. “Thought for Food: A Study of Written Instructions.” Symbolic Interactions 9: 201-216, 1986.

(4) Calling the recipe “diabolically cruel,” Kitchiner quotes it from Johann Jacob Wecker’s Eighteen Books of the Secrets of Art and Nature, first published in English in 1582 (?), who attributes it to a cook named “Mizald.”This individual – whose full name was Antonius Mizaldus, a 16th century Parisian physician and botanist – may well be a rather unreliable source, because he also wrote that piling sweet basil leaves on a dung heap would soon result in a nest of scorpions or asps. See also Dr. William Kitchiner: Regency Eccentric – Author of “The Cook’s Oracle,” by Tom Bridge and Colin Cooper English. London : Southover Press, 1992.

(5) Fisher, M. F. K. “The Anatomy of a Recipe,” With Bold Knife &Fork. New York: A Paragon Book, 1968, pp. 13 – 24.

(6) Floyd, Janet and Forster, Laurel. “The Recipe in it Cultural Context.” In: The Recipe Reader: Narratives, Contexts, Traditions, edited by Janet Floyd and Laurel Forster. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

(7) Willan, Anne. “The Writing of a Recipe,” The Cookbook Library. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012, pp. 6 – 11.

(8) The Book of Sent Soví: Medieval Recipes from Catalonia (Textos B), edited by Joan Santanach. Barcelona: Barcino-Tamesis, 2008.

(9) Lady Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book, edited by Hilary Spurling. New York: Elizabeth Sifton Books Viking, 1986, p. 91.

© 2014 C. Bertelsen

Brilliant. Love they description.

Yes, Tony, yes! You are spot-on; I love that phrase and welcome opportunities to use it. The dud that said that, well, yes, let’s be charitable … .

I select recipe books; at church fetes, charity shops, and secondhand bookshops. Sometimes new books, like Ny Nordisk Hverdagsmad – [an easier approach to Noma than Noma].

Selecting carefully, I do notice things. My AliBab was used for real cooking. My Mapie Toulouse-Lautrec was used. Elizabeth Davids – all the paperback versions are falling apart from use. Gravy blotches and cracked spines everywhere.

But, at a fete or a secondhand bookshop, I notice the pretty-pretty books, [colour photos, ingredient list, method and a number of stars telling you how easy it is]. They are all pretty clean and unused! It seems to me, that if a pretty-pretty book turns up at a fete, the owner is saying “this book is useless”.

That tells me something. It should also tell your gent at the head of the table. Whatever social inferences he might elaborate from such pretty books, well …. …. let us be charitable.

It’s a very period book. I first bought it in the ’70’s and found it in a used book store about 5 years ago. It’s an underground cookbook written by Ita Jones. My copy is by Random House. Very different from Honey from a Weed but I like the essays about food and philosophy.

Honey From a Weed is a real pleasure, isn’t it? I don’t know Grub Bag, will take a look. Thanks for sharing!

I love reading old cookbooks – medieval to modern. Two of my favorites are Honey from a Weed and the Grub Bag – very different and yet filled with the love of cooking and how important it is. redacting medieval recipes is a lot of fun when you get a group of people all trying out the same recipe and finding variation with the resulting offerings…