French food, like all cuisines, is not immune to change. Recall, if you will, La Varenne. And take a quick look at some of the numerous and new French-related cookbooks appearing recently.* Conversations about the dismal and declining state of French cooking arise continually and experts try to reassure us that, au contraire, we will always have Paris or at least les frites.

French food, like all cuisines, is not immune to change. Recall, if you will, La Varenne. And take a quick look at some of the numerous and new French-related cookbooks appearing recently.* Conversations about the dismal and declining state of French cooking arise continually and experts try to reassure us that, au contraire, we will always have Paris or at least les frites.

Ah, tradition … what a ball-and-chain it can be.

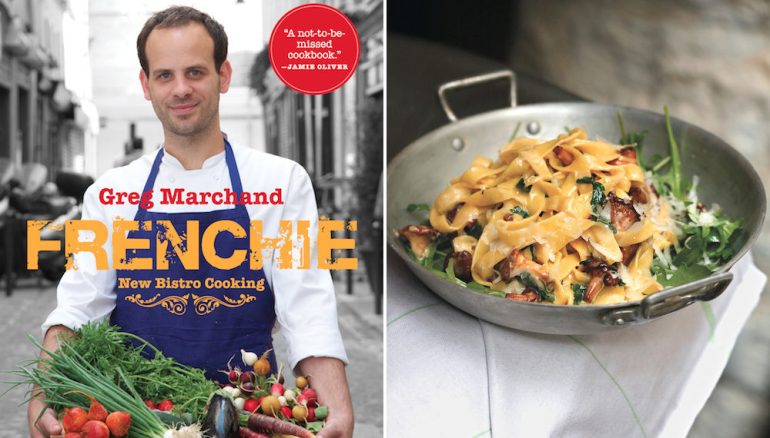

French chef Greg Marchand’s new cookbook, Frenchie,** will strike a decisive blow for those whose idea of French cuisine relies on images conjured up by Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast (1964, revised 2009), A.J. Liebling’s Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris (1962), or even M.F.K. Fisher’s glorious work.

Marchand’s life story, at least the early version, reads like a Dickens novel. Raised in an orphanage in Nantes, and after scrambling through cooking school on his own dime and steam, Marchand landed on his feet, spending 10 years cooking in London, Hong Kong, Spain, and New York. He opened Frenchie, his small bistro-like restaurant on the Rue du Nil, in 2009 with €10,000 in seed money. The name “Frenchie” comes from the nickname Jamie Oliver bestowed on him when Marchand worked at Fifteen, one of Oliver’s restaurants.

This cookbook, while nothing like The Ethnic Paris Cookbook published a few years back by Charlotte Puckette and Olivia Kiang-Snaije, reflects the influence of the world’s cuisines on what some have thought to be an unchangeable icon: French bourgeois cooking.

Right out of the gate, the first recipe – “Foie Gras with Cherry Chutney” – calls for odd bits not likely to be hovering about in most people’s pantries:

Foie gras

Brandied cherries

2.5 pounds Bing cherries

Each of the 32 recipes actually comprises several recipes, with recipe titles appearing in several different fonts. Many of these recipes-within-a-recipe borrow ingredients heavily from the cuisines that formed Marchand during his global-trotting years, most particularly it seems the time he stood over the stoves in Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s Vong at the Mandarin Oriental in Hong Kong. Take the pickled mustard seeds for example used as a garnish. The recipe takes a so-called traditional French ingredient – mustard seeds – and seasons them with sugar and rice vinegar.

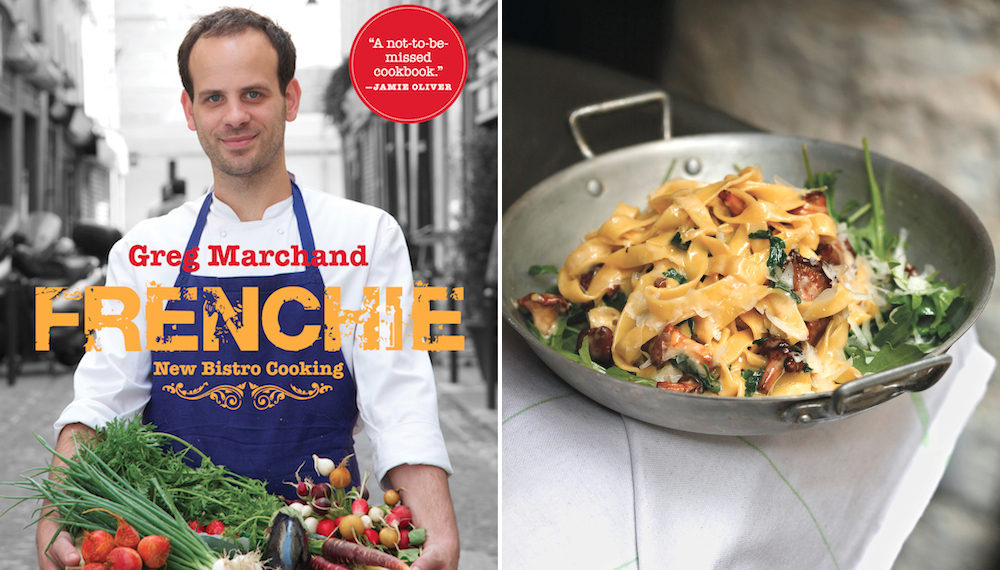

Arranged by the seasons and filled with gorgeous photos, both of finished dishes and the cooking process, Frenchie at first seems fairly accessible for the average home cook, which is what Marchand dreamt of in the conception of the book, saying “But I didn’t write this book to show you what I could do: I wanted to show you what you can do.”

Now, if you live in New York or any other large city, and your wallet is plump, Marchand hits it out of the park: Frenchie will be a book you can cook from and love. If you live, as I do, in the back of the beyond, then you might be able to handle bits and pieces. You will definitely be striking up a close relationship with your UPS driver, because some of the recipes require the following ingredients, none of which adorn the shelves of most local supermarkets:

Piment d’Esplette, Wild garlic leaves, Vin Jaune (Savagnin), Farro, Trout roe, Fava beans in the shell, Green mango, Amarena cherries, Verbena, Sherry vinegar, Red currants, Almonds in the shell, Italian 00 flour, Fresh chanterelles, Stovetop smoker/smoking chips, Borage flowers, Salt-packed anchovies, Purple basil, Smoked mozzarella, Wild strawberries, Serrano ham, Wild mushrooms, Mimolette cheese, Amaretti cookies, Sorrel leaves, Beef cheeks, Baby beets, Baby turnips, Pecorino pepato, Quinces, Sweet chestnut puree, Speck, Blood sausage, Burrata, Jerusalem artichokes, Kumquats, Celeriac, Duck breasts, Lychees, Speculoos, Passion fruit (fresh)

Still, this is a chef’s book. You’ll recognize that by all the prep required for cooking the dishes. If you love to cook – and I do – it will be worth hunting down the ingredients and then playing in the kitchen. Without a large brigade de cuisine to back you up, you’ll be at the stove or cutting board for a while.à

Probably the most accessible recipe is on p. 116: “Roast Pork, Red Beet Broth, and Pickled Mustard Seeds.” But follow this link to a salad recipe from Frenchie for an idea of what the recipes are all about: Salad of Bitter Greens with Speck and Clementines.

For me, the thrill of Marchand’s book and his restaurant lies in the incorporation of other, more global flavors and textures into his dishes, while still holding on to many French nuances.

I wonder if it is valid to ask whether or not Marchand’s experience serves as a model for how cuisines change? Or even evolve? His culinary experience prior to returning to France in 2009 opened up his palate to a world-wide panoply of food and flavors. As David Burton writes in Gastronomic Encounters,*** “Since its appearance in the mid-seventeenth century, modern French cuisine has been famously anti-chilli and spices, having based its world-wide pre-eminence on the championing of herbs, salt, pepper, and acidic flavors to the exclusion of spices, saffron, and sugar. … And so things continued for the next three centuries. … As chef de cuisine of Lucas Carlton in Paris, [Alain] Senderens is famous for introducing spices and aromatics in ways that often seem inspired by the cooking of France’s former colonies … .” (pp. 55-57) Marchand includes a recipe for Chile Oil in his book, paired with a watermelon-ricotta salad reminiscent of a Greek popular salad touted by American TV chefs like Paula Deen and Ina Garten.

Burton goes on to say, “In the manifold styles designated for instance as à la creole or à la catalane, the French dish is no more than an exotic representation of the Other, the influences of foreign cuisines being primarily at the level of flavourings rather than in the areas of technique and method. … Algerian techniques have hardly dented insular French cooking.” (p. 61)

More ink needs to be spilled on this topic, because although Marchand seasons his dishes lavishly with flavors far removed from what we think of as traditional French cuisine, he utilizes mostly French culinary techniques in his execution of his dishes. And yet who can say where those flavors will ultimately lead?

*La Mère Brazier; À la Mère de Famille; AlainDucasse Cooking for Kids; My Paris Kitchen; Stéphane Reynaud’s Book of Tripe; La Crêpe Nanou Cookbook; Buvette; From Scratch

**Frenchie, by Greg Marchand (Artisan, 2014, 144 pages, $22.95) Principal photography by Djamel Dine Zitout. Includes a good index, with recipe titles, as well as ingredients, making it easy to find specific recipes for specific ingredients.

***Burton, David. “Curries and Couscous: Contrasting Colonial Legacies in French and British Cooking.” In: Gastronomic Encounters, edited by Lynn Martin and Barbara Santich (Brompton, South Australia: East

Books; 2004..

© 2014 C. Bertelsen

You must be logged in to post a comment.