Being alive, being in the world has always been a desperate struggle for survival. We sometimes dub this state of affairs “dog-eat-dog.”

However, the root of this phrase actually means the opposite in its original Latin: canis caninam non est. Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro recorded this Latin proverb in his De Lingua Latin (About the Latin Language) in 43 BC. Dogs do NOT eat the flesh of dogs. Better yet, dogs do not prey on their own kind. They run in packs, a survival mechanism.

“The current phrasal form would not appear until the 19th century. “Possibly the earliest variation of ‘a dog-eat-dog world‘ occurred in ‘The Examiner’ on December 5, 1813. Referring to trade and commerce, the quote reads, “‘Dog eat dog,’ is now our commercial motto and practice.’ By the 20th century, this modern permutation had become the norm.”

Until the invention of the telegraph, most people in the past only read about the news days or even weeks later in a newspaper. The 24/7 news cycle ensures we all come face-to-face with events and happenings near and far.

Humans, however, will eat each other, if not in the literal sense, at least in the metaphorical sense, the Donner party and Jamestown being exceptions among many. Not to mention the voraciousness of capitalism, murder, and other atrocities.

Atrocities such as war.

And so it’s no surprise I’ve been thinking a lot about Charles Darwin’s “survival of the fittest” theory.

Survival in wartime is no easy thing. The current crises in Ukraine and Gaza, now in the news 24/7, illustrate in real time how difficult survival is for civilians – and animals – caught up in armed conflicts.

But my preoccupation with this topic is not just because of the current news cycle.

I’ve been deep-diving into research about the lead-up to World War II and the ensuing carnage. Perfect examples of humans preying on each other emerge everywhere I look in writings about that war.

But human nature being what it is, war and conflict historically – and sadly – seem more normal than peace.

There’s no shortage of literature on this topic concerning World War II. For most people today, however, it’s as ancient as Roman Italy or Homer’s Greece. I’m just going to share a few here with you.

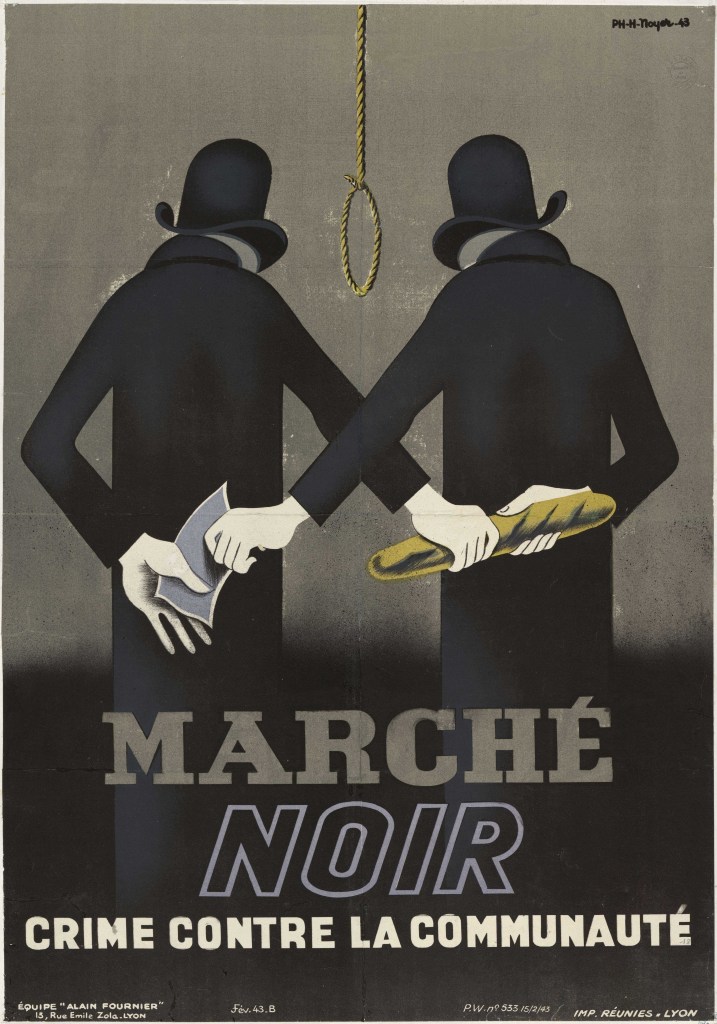

Kenneth Mouré’s Marché Noir: The Economy of Survival in Second World War France examines the black market in France during the war. With brief quotes about food shortages, queuing for a limp carrot or moldy potatoes, and the struggle to keep ration coupons safe, Mouré’s book paints a precisely researched chronicle of the black market in France, ostensibly a crime with severe repercussions for those engaging in subterfuge.

Both French and German authorities couldn’t keep up with those who engaged in the practice. Since the Germans – from generals to privates – viewed a posting in Paris as a vacation, certain restaurants were immune to the rules so that the occupiers could truly enjoy everything French, especially fabulous food.

It’s one thing to read a secondary source about World War II. But it’s quite another to read the personal, detailed accounts by people who lived during times of war.

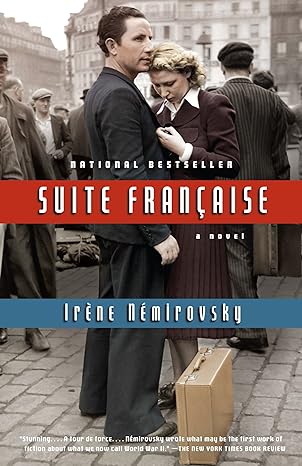

One example is Suite Française, a novel by well-known French writer Irène Némirovsky. It details the agony faced by many French-Jewish people during the German Occupation. Despite the fact that Némirovsky was a respected writer, she too died in Auschwitz. The novel – actually two novellas – appeared sixty-four years after she wrote it because her daughter feared reading it would dredge up old and difficult memories.

Classified as fiction, Suite Française describes daily life under the German Occupation in detail. It’s actually anything but. Many critics believe Némirovsky’s account mirrors much of her own experience before the Nazis transported her to Auschwitz. The Nazis enacted racial laws against Jewish people, including strict rationing. Jews were allowed to shop for food only at the end of the day when most of the scarce food supplies were gone.

Then there’s The Journal of Hélène Berr. Written for her fiancé, Jean Morawiecki, and saved by her family’s cook, Andree Bardiau, the journal ended up in the hands of an uncle. Finally, her niece, Mariette Job, got a hold of it and published it in 2008. Berr was a gifted writer who wrote, “I know why I am writing this diary. I know I want it to be given to Jean if I am not there when he comes back. [He did return.] I do not want to vanish without him knowing what my thoughts were during his absence, or at least a good part of them.” She devoted a lot of time trying to help Jewish children from being deported east until she found herself in a cattle car going east, to Auschwitz.

On February 15, 1944, she wrote her last entry: “Horror! Horror! Horror!” A few weeks later, on March 8, 1944, the Nazis arrested her and her family.

And lest we become too complacent, yes, it COULD well happen here.

__________________________________________

For more reading about personal experiences during World War II France, start HERE.

I remember!

Great! Have you read it yet?

Sounds like a powerful book. I’ve reserved it at the library.

Thanks so much for the comments. I really appreciate that. Yes! I remember indexing that book.

You say so much in such a meaningful way in this essay, Cynthia. I feel blessed to have discovered you via the food world. (As you may recall, you indexed “Seafood Cooking for Dummies.”) You’ve given us (me) so much to digest in this piece, but your phrase that is seared into my mind is your last one: “and lest we become too complacent….”