As a writer, I find inspiration in so many places. Gossip whispered at parties, current newspaper reportage, anecdotes revealed by family members over a few mugs of coffee, the odd remark overheard in a doctor’s waiting room or in an elevator, and on and on.

History, however, provides me with more than enough material to spark my imagination. Indefinitely.

My muse? The Greek goddess Clio.

One of nine ancient Greek muses of the arts and literature, Clio’s name signifies “to make famous” or “to celebrate.”

Nine Muses Monument in Skopje, Macedonia (Adobe Stock photo, Мария Михалева)

And that is what the writing of history does.

But perhaps a better description of Clio is that she ultimately acts to make the past known. That trait lies behind the current battle over the past in the United States. What story is the true one, whose story will rise to the top? African slavery stains nearly every era of American history. A glance at any publisher’s list these days proves that Clio is hard at work inspiring writers to dig deeper, to go beyond the received wisdom, the work of earlier historians.

“Revisionism” is the word historians grasp onto when it becomes clear there’s more to be studied, interpreted, and pondered.

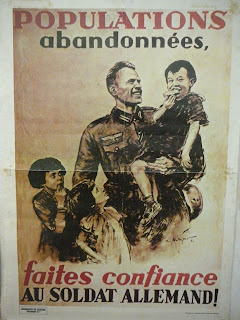

In France, another, more recent stain faces scrutiny. French collaboration with the Nazis during the Occupation between 1940 and 1945 is a topic still taboo, still rankling, still fraught with many emotions, especially guilt. And shame.

History, they say, tells the story of the victors. In the case of France, that’s true. General Charles De Gaulle, virtually unknown in France prior to the Occupation, took on the role of leading the Free French from London. His broadcast on June 18, 1940, came four days after the Nazis marched into Paris unopposed. A legend grew up around that speech, which De Gaulle himself perpetuated in his 1954 Mémoires de guerre (War Memoirs). It is clear, however, that he did urge his fellow countrymen to resist the Nazis, saying at the end of the speech “Whatever happens, the flame of the French resistance must not be extinguished and will not be extinguished.” The BBC gave the Free French five minutes per night to broadcast, and that soon became another tool in the fight against the Nazis, as code phrases alerted various resistance cells of activities, giving the green light to various actions.

Nowadays, popular adage has it that from the very beginning the French resisted the German occupiers. Yes, many did, in small ways, via leaflets and graffiti. But the overall feeling in France at that time appeared to be shame. At the loss of their freedom, the weakness of their defense at the Maginot Line, and the relief of knowing that the gruesome battles of the Great War would not be repeated on French soil. Not until the Allied assault on the Normandy Beaches on D-Day, June 6, 1944, did the real Resistance begin, organized and supplied by the Americans and the British with ample munitions and agents.

German Propaganda Poster from early days of the Occcupation.

The whole story of France under the Occupation remains murky. Despite mountains of books published, oral histories saved, museums devoted to the Resistance, and opinion pieces written, much remains to be done.

Clio will have her way, eventually.

(My current writing project — Season of the Wolf — pertains to WWII Paris.)

Gary, yes, yes, yes. I agree,

Marie, Thanks! You are so right, history is a goldmine for writers, whether of fiction or non-fiction.

History holds so many stories. Thank you, Clio!

Let’s hope that Clio will have her way HERE… and soon.

>