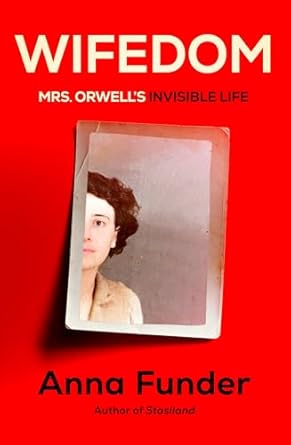

One day in the spring of 2023, I learned that writer Anna Funder would soon be publishing Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life with Penguin Random House. Of course, I pre-ordered it for my Kindle.

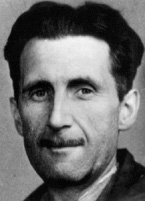

After reading all the existing biographies of George Orwell, Funder realized that Orwell’s wife, Eileen Blair, only merited a mention or a footnote in all of those books. And Orwell himself rarely mentioned her.

Like Funder, George Orwell’s work always seemed special to me, for I grew up in the thick of the Cold War. Each day – or so it seemed – was filled with disdain for Communism. My father favored films about the fight against Fascism during World War II. He’d just finished pilot training with the Army Air Force when the war ended and was demobbed.

Ironically, it was Orwell’s essay, “In Defence of English Cooking,” that cemented my fascination with this writer, a man who wrote copiously and died at forty-six of tuberculosis.

I first learned of George Orwell – born Eric Arthur Blair in Motihari, India to British parents – in a high school classroom in eastern Washington State. My class, probably in our junior year, but I could be mistaken, found ourselves reading Orwell’s 1984. Big Brother stayed with me. And Animal Farm, too. The brutish pigs in charge reminded me of what I’d read in Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Sometimes I thought things that shouldn’t cross the mind of a child. Even a sixteen-year-old mind. To think that somehow, in the future, someone might read my mind, literally seeing my thoughts, frankly terrified me. At the time I read of Winston Smith’s misadventures, the real 1984 – the year itself on the Gregorian calendar – seemed light years away.

All too soon, the year 1984 came and went without too much drama. And Orwell’s nightmarish scenarios faded somewhat when the Soviet Union went the way of the Dodo bird in early 1992.

The term “Orwellian” soon crept into the English language, beginning in 1950, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. I don’t see it in my 2020 edition of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. But according to the New York Times, it’s “the most widely used adjective derived from the name of a modern writer … “

The current political climate conjures up Orwellian visions. A certain political party espouses a frighteningly dismissive and disturbing attitude toward women, quite similar to what transpired in 1984.

That brings me to Anna Funder’s book. And Eileen Blair, as she called herself.*

Anna Funder’s unique look at Orwell’s wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy Blair, offers another take on George Orwell. And it’s not at all flattering. Many women will identify with Eileen’s plight because the cultural attitude toward women of the times kept her from achieving her full potential.

I mean full-blown misogyny trailed her for the whole of her life. Because that was true for most women.

Orwell’s work, for example, Homage to Catalonia, leaves Eileen out of the story. Yet Funder digs through archives and finds Eileen. Six letters unearthed in 2005 made Funder’s work easier. She weaves together biographical material with the letters, threading in fictional and imaginary scenes of interactions between Orwell and Eileen.

Eileen’s influence reached deeply into his work. Friends suggested Orwell’s writing changed after his marriage. Although Eileen died in 1945 during surgery for what probably were fibroids, anemic and unable to sustain the stress of the procedure, her poem, “1984,” became the title of Orwell’s most famous book, published four years after her death.

She wrote the following poem in 1933, the year before she met Orwell, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of her high school in Sunderland, UK. He was two years older than she. Eileen worked as a journalist, editor, and proofreader in London after her graduation in 1927 from Oxford, where she read English. So, in her own right, Eileen comes across as highly intelligent and talented. Orwell attended Eton but never went on to university, having failed to secure a scholarship. Eileen typed his manuscripts and probably slipped in corrections here and there due to her expertise with the English language.

Death

Synthetic winds have blown away

Material dust, but this one room

Rebukes the constant violet ray

And dustless sheds a dusty doom.

Wrecked on the outmoded past

Lie North and Hillard, Virgil, Horace,

Shakespeare’s bones are quiet at last.

Dead as Yeats or William Morris.

Have not the inmates earned their rest?

A hundred circles traversed they

Complaining of the classic quest

And, each inevitable day,

Illogically trying to place

A ball within an empty space.

Birth

Every loss is now a gain

For every chance must follow reason.

A crystal palace meets the rain

That falls at its appointed season.

No book disturbs the lucid line

For sun-bronzed scholars tune their thought

To Telepathic Station 9

From which they know just what they ought:

The useful sciences; the arts

Of telesalesmanship and Spanish

As registered in Western parts;

Mental cremation that shall banish

Relics, philosophies and colds –

Mañana-minded ten-year-olds.

The Phoenix

Worlds have died that they may live,

May plume again their fairest feathers

And in their clearest songs may give

Welcome to all spontaneous weathers.

Bacon’s colleague is called Einstein,

Huxley shares Platonic food,

Violet rays are only sunshine

Christened in the modern mood.

In this house if in no other

Past and future may agree,

Each herself, but each the other

In a curious harmony,

Finding both a proper place

In the silken gown’s embrace.

Sylvia Topp’s more traditional biography, Eileen: The Making of George Orwell, preceded Funder’s Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life. Funder does acknowledge Topp’s book in Wifedom.

Since I’ve long been an Orwell fan, reading Wifedom hurt. I could see myself in some ways through Eileen because of the ways I’ve also experienced misogyny. Truth be told, I suspect most women have, married or not. I found it painful, too, reading of Orwell’s difficulties in relationships.

Does knowing what a cad George Orwell could sometimes be change my opinion of him? In a way. But, like Anna Funder, I set aside some of my misgivings about the George Orwell she teases out of the archives and between the lines of the biographies, all written by men. The revelations about George Orwell’s attitude toward the female sex, in the end, were not surprising. It’s tough to learn that one’s idol might have had feet of clay.

What was surprising was Eileen and her solid, rich presence in his life as a writer.

Using many tools – solid research, primary sources, and snippets of fictional interpretation, Anna Funder’s Wifedom brings Eileen to vivid life, along with others in Orwell’s circle of friends and acquaintances.

However …

One thing that strikes me about Wifedom is Funder’s tendency to perhaps judge Orwell by today’s mores, not recalling the times in which he and Eileen lived. Born in 1966, and coming of age in the 1980s, Funder enjoyed young womanhood without many of the gender restrictions that Eileen faced as a young woman in 1920s and 1930s. I call this “presentism,” the practice of viewing the past through the lens of the present.

In the Spring 2024 journal of The Orwell Society, I subsequently read a review of Wifedom and its impact on Orwellian studies. Despite Funder’s accusations of plagiarism and sexism in Wifedom, my feelings about Orwell’s work remain unchanged. In many ways, I would say Eileen herself would be appalled at the vitriol unleashed by Wifedom, because she likely recognized her husband’s genius. Otherwise, the times aside, why did she put up with it all?

Only time will tell if Wifedom shatters Orwell’s reputation.

I feel that it will not.

___________________

*Orwell’s second wife Sonia Brownell, whom he married three months before he died, became his literary executor and passed away in 1980 at age 62. After that, Eileen’s and George’s adopted son, Richard Horatio Blair, became the literary executor.

Thanks, Wendy. It’s well-written and timely, but as I said, a tinge of present-day thinking overlies her take on the Orwell/Blair marriage.

Let me know what you think when you’ve read it. Yes, many writers depend on their spouses as proofreaders, editors, and a place to bounce ideas off of.

I have the book Wifedom awaiting me on my nightstand. I haven’t read it yet. It’s possible that many writers depended on their spouses as editors. I wish Eileen could have lived longer and written more.

Interesting review – I’ll have to get this book. Thank you for this!