In today’s America, there’s a certain glorification of tyrants, certain ideologies. Most of the time, when reading of Germany’s Nazis and World War II, it’s easy to lump people together, to believe that everyone followed the party line.

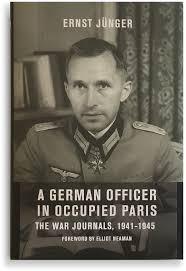

One exception to that, I recently discovered while doing research for my new writing project, was Ernst Jünger (1895-1998).

Who was Ernst Jünger?

An insightful and controversial and fascinating German writer, Jünger’s life intertwined with the rise of Nazi Germany. He trod a fine line between Party ideology and his own adventurous thoughts and actions, evident from a very early age. Expelled from various schools and then lying about his age, he joined the French Foreign Legion in 1913. Escaping later from a camp near Oran, he was captured and held until his father arranged his release through the German Foreign Office. In 1914, he volunteered for the Seventy-Third Regiment of General Field Marshall Prince Albrecht von Preussen and fought in the Great War (World War I).

He wrote a best-selling book about his experiences. And the book is still in print – Storm of Steel. Despite his early fervent militarism and fourteen wounds sustained in World War I, for which he was awarded the Pour le Mérite, Jünger signed up with his old unit at the outbreak of World War II. And that came as a surprise to me, given he believed Hilter to be a dangerous idiot. Goebbels later banned Jünger’s allegorical and fantastical novel, On the Marble Cliffs, because it mocked the rise of the Nazis in particular and fascism in general.

But instead of the trenches and the front, Jünger spent most of the war at a desk at the Hôtel Majestic on Avenue Kléber in Paris. His duties included seeking intelligence on the Resistance and Allied military movements. Billeted at the nearby opulent Raphael, his whole life in Paris revolved around everything luxurious, including food. Jünger offers a surprising alternative to the stereotypes of the brutal, gore-thirsty Nazis found in most literature. Up to a point, he reminds me a bit of the character Werner Pfennig in Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See.

Jünger’s Diaries read at times like mere recitations of his day-to-day activities. But many entries are frankly spellbinding, often stuffed with the dreams he records with astonishing details and the fruits of his extensive reading into the classics and other monumental literature. An avowed Francophile, he, of course, includes French literature as well. With just a high school education, Jünger nevertheless comes across as extremely well-educated and accepted by the aristocratic officers surrounding him.

The Diaries also paint a portrait of Paris as an occupied city. But because of his privileged status, little of the suffering of the average French person seems to have caught his attention. However, he wrote at one point, “Never for a moment may I forget that I am surrounded by unfortunate people who endure the greatest suffering.” His lover in Paris was a German-Jewish doctor, Sophie Ravoux, although he had a wife and two children back in Germany. He passed messages about deportations to the resistance and worked to hide Jews when he could.

He recounts many lunches and dinners at the Ritz, Prunier, and other similar gastronomic temples of Paris, as well as intellectual salons frequented by French luminaries such as Jean Cocteau and other pro-German French people.

But all along, Jünger was very much anti-democracy, his thoughts surprisingly relevant for our own turbulent times.

Jünger belonged, albeit low-key, to the group of anti-Hitler German military. His diary writings included a code name for Hilter: Kniébolo. Ironically, Jünger was never singled out as a member of either the Rommel Plan or the Stauffenberg “Valkyrie,” both plots to assassinate Hitler. He never felt that direct action would bring down the Nazi regime but that it would implode on itself. Which it did. The chaos at the war’s end meant he left on one of the last trains out of France and back to his home in Saxony.

Telling the story of the German occupation quite naturally falls on the plight of the Parisians – Jews and non-Jews – during the dark years when the City of Lights no longer gleamed. But thanks to writers like Jünger, in his Diaries we spot glimmers that round out the period of the German occupation of France – what life was like for the occupiers, or at least for the officers.

In Jünger’s words, “My situation is that of a man who dwells in the desert between a demon and a corpse.”

__________________________

The title of this post relates to Emily Dickinson’s poem, Tell all the truth but tell it slant:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant …

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

For more about Jünger, take a look at this list to see how prolific a writer he was.

They were not all monsters; many were just ordinary people caught up in a cruel system. Very sorry about your great-uncle. I assume he spoke German? I’m glad he wsn’t treated poorly. However, many of the letters sent out never mentioned hardships because the Germans would not have allowed any negative comments. Were those comments in letters after the war?

How interesting Cynthia. My Alsatian great uncle was a prisoner on the island of Alderney. He built battlements around the island for the Germans. He mentioned in his letters that he was treating pretty well by the Nazis (they needed strong young men.)

Nice to hear from you.

Kitty Morse

Sent from my iPad