Nature is a Haunted House – but Art – a House that tries to be haunted.

~ Emily Dickinson

From my vantage point on the third floor of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, I spy on the ant-like pedestrians scampering below, frantically dodging raindrops and rude taxis. Tiny moving sculptures, limbs pulled by an invisible puppeteer.

My watch flips to another number. I check the time again.

Where is that man?

A rustling of air behind me, a mumbling voice in my ear. “Sorry, sorry, I … .” Late, as usual, he kisses the back of my neck while shaking his limp black umbrella. Water droplets scatter over the black marble floor. I wait for the excuse.

What would it be this time?

The D.C. metro, it seems, stopped for longer than usual at Federal Triangle.

I grab his umbrella-free hand and pull him across the gallery’s threshold, black marble to white, anxious to disappear once again into the magical world of Remedios Varo.

Spaniard. Female. Surrealist painter. Exile.

And my Muse.

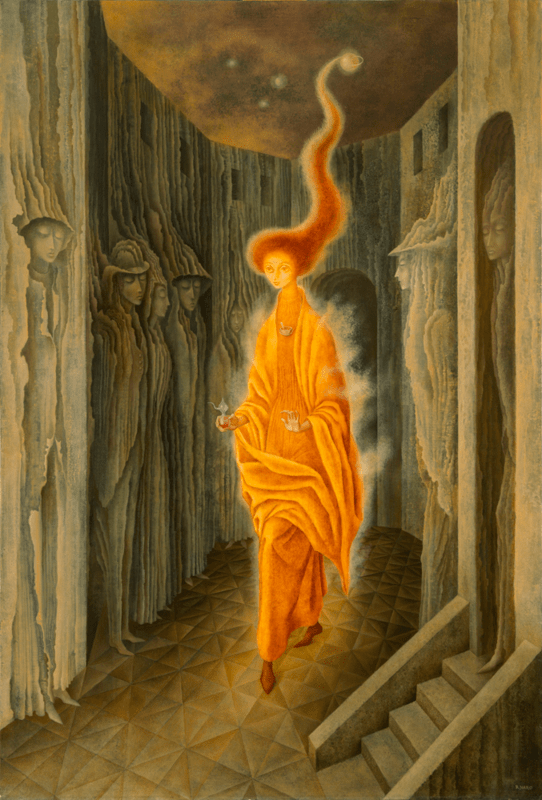

Just inside the wide arched doorway, there she is, in a stunning self-portrait. Red hair strung long and high against an inky sky, swirling toward the stars, swathed in flowing garments the many hues of incandescent fires, of sailors’ mornings. So vivid, that imagery of flaming energy, I thought I’d burst into flame myself just by reaching toward the canvas. Fingertip to fingertip, Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam” incarnate.

I yearn to touch it, to caress it. But I dare not.

Do Not Touch, the little white sign warns.

Security cameras track my every move, I know. Ambling guards circle the corridors. I pause, transported to another time, another place, when I first heard of Remedios Varo and sensed the power of art to haunt. When I first saw “The Call.”

And this woman enveloped in the gilt frame, who’d haunted me for years. And still does.

Mexico City, so long ago. When it all began. A late November day. A break from classes. All Souls’ Day. The final third of the triptych of Día de los Muertos. I’d sat the day before in the middle of a cemetery, dried yellow leaves drifting through frigid air, red candles flickering on crumbling cement slabs shrouding tombs of the dearly departed. Grandparents of my friend Celina. Marigolds the color of April bees covered other crypts, puffy like furry winter coats. Children skipped and tumbled through narrow spaces between masses of graves, chewing on twinkling sugar skulls marked with their names, their white teeth matching those of the skulls: Silvia, Jorge, Pablo, Francisco. A sense of otherworldliness hung in the air, as ethereal as the smoke from the small fires pouring skyward, lit as darkness crept through the crisp cold air.

When I first saw “The Call,” that same sense of the otherworldly possessed me. Mysterious details in the painting drew me like a magnet tugging at metal filings. I instantly recognized something deep and primeval. Until then, my knowledge of art revolved around Norman Rockwell’s paintings decorating The Saturday Evening Post covers.

The fiery figure in the painting emerged from a lengthy and dark tunnel-like corridor, stepping into a light shining before her. I stuck my face close to a small white plaque, covered with a curator’s words, telling only a fraction of the story:

Although Varo rejected her Catholic upbringing as being over proscriptive, she spent much of her life searching for mystical inspiration from alternative sources, including the writings of Carl Jung and Western and Eastern hermetic philosophies.

Nowhere is this more eloquently stated than in her self-portrait The Call (1961), which features the artist, radiant with cosmic energy conveyed through her flowing red hair, wearing an alchemist’s mortar, and holding a beaker filled with transformative elixir. Striding through a passageway lined with figures locked in colorless stasis, Varo as the quintessential hero asserts the rightness of her quest and the planetary inspiration that moves her.

I sensed hints of myself in “The Call.” The energy flowing from the figure in red, her intensity, all mine, too. For me, the people embedded in the beige and brown walls, staring out straight ahead, rigid, unseeing, frozen in time and place, represented those who failed to break out of society’s rigid mold, those who said “yes” to expectations. People who hesitated to grab onto life with both hands, not questioning the “should,” the “ought.”

Outside the Museo Nacional de Arte, dramatic bronze sculptures towered over the cracks, and crabgrass punctuated the worn sidewalk. Diesel fumes flooded my nostrils as dozens of crowded busses puffed soupy, acrid soot into the sky. With every roaring acceleration, the cuffs of my white blouse turned blacker, grimier. Rings of soot formed inside the collar. In front of me, women draped in rebozos the colors of late-summer rainbows squatted before small charcoal-burning braziers, hawking chalupas, thick hand-patted corn tortillas piled high with shredded pork and mashed green avocado.

None of those aromas or sights erased what I’d just seen. Remedios Varo’s magical world possessed me, seduced me. Her art sucked me into another dimension. There, the world seemed softer, less focused.

“The Call” haunted me then, on that street in the heart of Mexico.

And it still did 25 years later. In that museum in Washington D.C., a feeling of déjà vu swept over me like a rebozo, suffusing me with a sensation of warmth. Why does the work of any particular artist or writer bore its way into one’s psyche, taking up residence like a persistent squatter? It’s as if something empty fills up inside when the right words and images click into place. As if a missing piece of a jigsaw puzzle suddenly slips into the precise slot.

Remedios Varo provides a missing piece of my life puzzle. Her work embodies what Joseph Campbell labeled a mythological journey. She plays the role of the Hero in that journey. “The Call” mirrored Campbell’s words: “[D]estiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown.”

Remedios Varo became my Virgil.

I reach for him, tuck my hand into the crook of his elbow.

And so arm in arm we walk out into the rain.

After that rainy day in Washington, I hung four cheap reproductions of her paintings in my house. A small refrigerator magnet of “The Call” next to my computer. A larger version suspended at eye level on the wall by my office door. Every time I look at those stand-ins for the real thing, I remember what Remedios Varo taught me through her haunting art:

Life is a journey. The road winds and curves and even sometimes ends.

But the quest never stops.

For more about Remedios Varo’s life, see Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys, by Janet A. Kaplan.

Wow! Her paintings are so intriguing, hauntingly so.